In an opinion released on Thursday, the Tennessee Supreme Court answered a certified question of law from the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in the high-profile case of Cyntoia Brown, the juvenile sex trafficking victim who received a life sentence after being convicted of murdering a John. The Court’s opinion concluded—unanimously and correctly by any reasonable determination—that Ms. Brown will become eligible for parole after serving 51 years in prison.

It should be noted that the Tennessee Supreme Court’s ruling that Ms. Brown is parole eligible after 51 years was the more lenient outcome available in her case—albeit not the one that Ms. Brown’s attorneys had sought for reasons unique to her circumstances. Nonetheless, a flood of national attention to Ms. Brown’s case and a significant misunderstanding of its posture led multiple commentators—Ana Navarro, for instance—to decry the Court’s ruling as “a travesty of justice,” which it most certainly was not:

Cynthia Brown was a 16 girl when she killed a 43 year-old man forcing her to have sex.

The Tennessee Supreme Court ordered she must serve 51 years.

THIS IS A TRAVESTY OF JUSTICE.

Folks, you need to flood Gov. @BillHaslam’s twitter feed and demand he do something about this. https://t.co/EUKdwQnS6J— Ana Navarro (@ananavarro) December 8, 2018

To put the fairness of her punishment in its proper context: Cyntoia Brown’s sentence is grossly unfair, and Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam should grant her clemency immediately. (People like Calvin Bryant and Randy Mills deserve clemency, too.) Indeed, Governor Haslam should have granted her clemency months ago when she first applied. Ms. Brown—a bright, capable young woman who was very much a victim herself and whose rehabilitation is no longer even questioned—has been punished enough, and her sentence should be commuted immediately to bring it into compliance with modern standards of decency.

As for her pending legal challenge, though: Ms. Brown’s case is far from unique. In fact, from a purely legal perspective, her sentence is considerably less severe than fourteen others in Tennessee. There is a material difference between a juvenile life without the possibility of parole sentence—which fourteen Tennessee defendants are serving right now—and a juvenile life with the possibility of parole sentence, which is what Ms. Brown received. (One of those defendants—who is serving three consecutive life without the possibility of parole sentences for felony-murder charges committed when he was 14—is the author’s client.) Specifically: A life with the possibility of parole sentence includes the possibility of parole, while a life without the possibility of parole sentence does not. The issue in Ms. Brown’s case—which the Tennessee Supreme Court has now resolved—was whether her sentence included the possibility of parole.

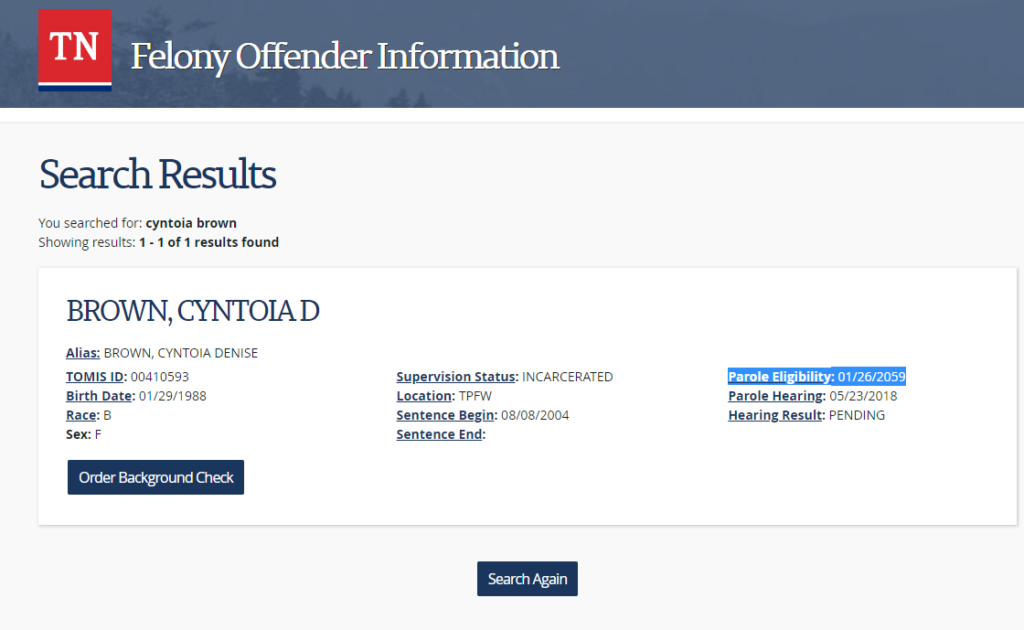

Ms. Brown’s trial court ruled that she would be eligible for parole after 51 years. There also has never been any doubt that this was the actual sentence that Ms. Brown received. In its sentencing order, her trial court specifically stated that Ms. Brown “must serve at least fifty-one (51) calendar years before she is eligible for release.” The Tennessee Department of Correction similarly notes that Ms. Brown is parole eligible:

Nonetheless, Ms. Brown’s federal habeas claim sought to convince the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit to hold that she was not eligible for parole at all. The claim—to put it mildly—was never likely to succeed. Nonetheless, in June, the Sixth Circuit gave the Tennessee Supreme Court the opportunity to clarify the perceived ambiguity in Tennessee’s sentencing scheme and determine whether or not Ms. Brown was parole eligible.

In its opinion on Thursday, the Tennessee Supreme Court concluded that Ms. Brown was indeed parole eligible. According to the Court, this result was dictated by Tennessee’s sentencing statutes, which the Tennessee Supreme Court determined were not in conflict. Even if Tennessee’s sentencing statutes were ambiguous, however, the “rule of lenity” would have required the same outcome. Under that rule, whenever there is an ambiguity in a criminal provision that can reasonably be interpreted in two ways—one that is more favorable to a defendant and one that is less favorable—precedent and fairness compel that the more lenient interpretation be applied.

Contrary to typical circumstances, Ms. Brown argued that she should have been given a sentence that was even harsher than the one she actually received. The reason why she lodged that claim? In a 2012 case—Miller v. Alabama—the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that juvenile life without parole sentences are presumptively unconstitutional. That decision was also held to be retroactive in 2016 following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Montgomery v. Louisiana. As a result, if Ms. Brown had received a life without the possibility of parole sentence, then she would (at least theoretically) be entitled to have her sentence remedied. In other words: Ms. Brown wanted the Sixth Circuit to hold that her sentence was even harsher than it was so that it would be presumptively unlawful. To date, however, it is worth noting that none of Tennessee’s fourteen actual juvenile life without parole defendants have had their presumptively unconstitutional sentences corrected in any regard.

Because the Tennessee Supreme Court has now determined—correctly and by necessity—that Ms. Brown is and always has been parole eligible, her entitlement to resentencing under Miller and Montgomery is not straightforward. She can, and will, continue to argue that she received a “de facto” life without parole sentence because few people will survive 51 years in prison. Nonetheless, anyone who decries the Tennessee Supreme Court’s clarification is, in a literal sense, demanding an even harsher outcome in her case: That Ms. Brown is never eligible for parole at all. The notion that the Tennessee Supreme Court’s failure to embrace that outcome is a “travesty of justice” is farcical, and outrage about the Court’s decision should be tempered accordingly.

Like ScotBlog? Join our email list or contact us here, or follow along on Twitter @Scot_Blog and facebook at https://www.facebook.com/scotblog.org