Over at the Litigation & Trial Blog, attorney Max Kennerly has penned an excellent piece on “The Unjust ‘Sporting Theory of Justice’ In Federal Courts.” The “sporting theory” at issue is a reference to a famous speech entitled “The Causes Of Popular Dissatisfaction With The Administration Of Justice,” which Roscoe Pound—then the Dean of Harvard Law School—delivered at the American Bar Association’s annual convention in 1906.

Pound’s essential premise was that, by the turn of the twentieth century, the American justice system had devolved into little more than a game that focused not on adjudicating controversies on their merits and meting out judgments that substantive justice compelled, but looked instead to whether litigants had successfully navigated procedural rules that had little bearing, if any, upon the actual case at bar. Pound decried:

“The inquiry is not: What do substantive law and justice require? Instead, the inquiry is: Have the rules of the game been carried out strictly? If any material infraction is discovered, just as the football rules put back the offending team five or ten or fifteen yards, as the case may be, our sporting theory of justice awards new trials, or reverses judgments, or sustains demurrers in the interest of regular play.”

None of this, of course, was to suggest that procedural rules are not important. Indeed, to the contrary, all agree that procedural rules—such as fair notice and a meaningful opportunity to be heard—are essential to protect substantive rights.

Frequently, however, procedural rules are distantly removed from substantive protections. Under such circumstances—particularly when a rule is unclear or an opposing litigant has not been harmed—the notion that someone should lose their day in court due to technical non-compliance is corrosive to the justice system’s fundamental purpose: To adjudicate the merits of controversies and dispense justice based on litigants’ substantive rights.

Frustratingly, despite many essential improvements over the past century that aimed to reform the justice game, many judges’ disinterest in providing substantive justice doggedly persists. Kennerly’s article provides some recent examples in federal court, but Tennessee is a similar offender. Tennessee’s intermediate appellate courts, in particular, have long jumped to dismiss substantive claims based on procedural technicalities that have little or no relation to litigants’ substantive rights—something that the Tennessee Supreme Court has repeatedly intervened to chastise over, and over, and over again.

Consider, for instance, the Court of Appeals’ 2014 opinion in Arden v. Kozawa—a wrongful death case that the Court of Appeals dismissed because the plaintiff had delivered notice to an opposing party using FedEx instead of USPS (the Tennessee Supreme Court sensibly reversed). Or this case from a few weeks ago, where the Court of Appeals declined to consider a litigant’s argument on appeal because—although the issue was raised in the litigant’s briefing—“an issue may be deemed waived when it is argued in the brief but is not designated as an issue in accordance with Tenn. R. App. P. 27(a)(4).” Alternatively, consider the host of hyper-technical dismissals in Health Care Liability Act cases for which this author has blasted the Court of Appeals for “undermin[ing] the fundamental purpose of the civil justice system as an institution.” None of these opinions is even remotely concerned with whether the substance of a litigant’s claim has merit. Instead, the judgments turn on whether the litigants involved adhered to substantively vacuous “rules of the game.”

The Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals, for its part, is just as guilty. Almost daily, defendants are treated to dismissive rulings based not on the merits of their claims, but based on (often unevenly applied) procedural flaws—waiver and abandonment, failure to preserve issues or exhaust remedies, failure to assert their claims quickly enough, and the like.

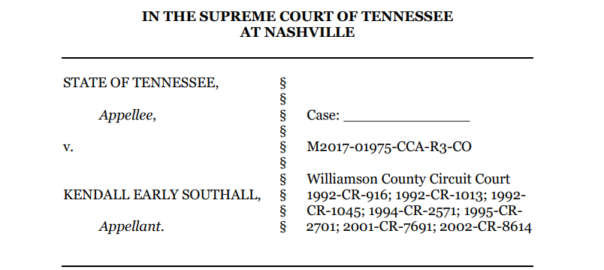

Perhaps no case better illustrates the Court of Criminal Appeals’ commitment to the justice game than this August 2018 case. There, a defendant sought to terminate his supposedly outstanding, decades-old court costs. He specifically invoked Tennessee’s ten-year statute of limitations for collecting on judgments as a defense to a District Attorney’s sudden and plainly retaliatory efforts to collect costs as many as twenty-six years after the fact. Unfortunately, the trial court dismissed the defendant’s claim on procedural grounds that both parties essentially agreed were wrong—finding that although the defendant had been served with multiple writs to execute on the judgments at issue, “no pending civil action existed” to collect on them. Thereafter, the defendant appealed.

In a series of previous cases—every single one of them involving a pro se litigant—the Court of Criminal Appeals had deprived similar litigants of their day in court and held that a denial of a motion to terminate court costs cannot be appealed under Tenn. R. App. P. 3(b), which governs criminal appeals.[1] Accordingly, the defendant made clear over and over again in his briefing that he was filing his appeal under Tenn. R. App. P. 3(a)—which governs civil appeals and guarantees litigants an appeal “as of right”—instead. The defendant’s argument also made particularly good sense in the context of his case, given that Tennessee law provides that taxes, costs, and fines that arise out of criminal cases are collectable “in the same manner as a judgment in a civil action.”[2] As an alternative to considering the merits of his appeal under Tenn. R. App. P. 3(a), though, pursuant to longstanding precedent that provides that the relief sought by a pleading—rather than the title assigned to it—controls its treatment, the defendant asked the Court of Criminal Appeals to convert his appeal into a catch-all writ of certiorari instead if Tenn. R. App. P. 3(a) did not afford him a right to appeal after all.[3]

In a cursory, four-page opinion, the Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed the defendant’s appeal on the basis that Tenn. R. App. P. 3(b)—Tennessee’s criminal appeal provision—did not allow it. (Tenn. R. App. P. 3(a) was never mentioned.) The Court also declined the defendant’s request to adjudicate the merits of his appeal as a writ of certiorari—even though the same court routinely extends the government that benefit under similar circumstances.

Given that—as noted above—the defendant had repeatedly indicated that he was appealing under Tenn. R. App. P. 3(a), not Tenn. R. App. P. 3(b), one reading of the Court of Criminal Appeals’ opinion might be that the Court misread the defendant’s claims. Alternatively, a less charitable conclusion might be that—in its haste to dismiss yet another defendant’s appeal on purely technical procedural grounds—the Court of Criminal Appeals didn’t read them at all.

Laudably, the Tennessee Supreme Court has frequently served as a bulwark against hyper-technical procedural dismissals of this sort. Consequently, time and again, it has intervened to reverse and remind Tennessee’s intermediate appellate courts that courts must not “exalt[] form over substance to deprive a party of his day in court and frustrat[e] the resolution of the litigation on the merits.”[4]

Encouragingly, Kendall Southall’s appeal to the Tennessee Supreme Court, in which he asks the Court to order the Court of Criminal Appeals to adjudicate the merits of his claims, still remains under review. For the sake of substantive justice—rather than just the sport of “the justice game”—everyone should hope that the Tennessee Supreme Court intervenes and affirms, yet again, the judiciary’s obligation not to “exalt form over substance”—something that our Supreme Court has repeatedly held that it “refuses to do.”[5]

Like ScotBlog? Join our email list or contact us here, or follow along on Twitter @Scot_Blog and facebook at https://www.facebook.com/scotblog.org

[1] See State v. Johnson, 56 S.W. 3d 44, 44 (Tenn. Crim. App. 2001) (“Christopher Joseph Johnson, pro se.”); State v. Hegel, No. E2015-00953-CCA-R3-CO, 2016 WL 3078657 (Tenn. Crim. App. May 23, 2016) (“James Frederick Hegel, pro se”); Boruff v. State, No. E2010-00772-CCA-R3CO, 2011 WL 846063 (Tenn. Crim. App. Mar. 10, 2011) (“Douglas Boruff, pro se”); Hood v. State, No. M2009-00661-CCA-R3-PC, 2010 WL 3244877 (Tenn. Crim. App. Aug. 18, 2010) (“Jonathon C. Hood, Clifton, Tennessee, pro se”); Lewis v. State, No. E2014-01376-CCA-WR-CO, 2015 WL 1611296 (Tenn. Crim. App. Apr. 7, 2015) (“Stephen W. Lewis, Wartburg, Tennessee, Pro Se”).

[2] Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-24-105(a).

[3] See, e.g., Norton v. Everhart, 895 S.W.2d 317, 319 (Tenn. 1995) (“the trial court should have treated the petition as one for a writ of certiorari. It is well settled that a trial court is not bound by the title of the pleading, but has the discretion to treat the pleading according to the relief sought.”); Estate of Doyle v. Hunt, 60 S.W.3d 838, 842 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2001) (“A trial court is not bound by the title of a pleading, but rather the court is to give effect to the pleading’s substance and treat it according to the relief sought therein.”); Hill v. Hill, No. M2006-01792-COA-R3CV, 2008 WL 110101, at *3 (Tenn. Ct. App. Jan. 9, 2008) (same).

[4] Jones v. Prof’l Motorcycle Escort Serv., L.L.C., 193 S.W.3d 564, 573 (Tenn. 2006). See also In re Akins, 87 S.W.3d 488, 495 (Tenn. 2002) (“we . . . avoid exalting form over substance.”); Childress v. Bennett, 816 S.W.2d 314, 316 (Tenn. 1991) (“it is the general rule that courts are reluctant to give effect to rules of procedure which seem harsh and unfair, and which prevent a litigant from having a claim adjudicated upon its merits”); City of Chattanooga v. Davis, 54 S.W.3d 248, 260 (Tenn. 2001) (overruling a prior decision that “exalted technical form over constitutional substance in a manner rarely seen elsewhere.”); State v. Henning, 975 S.W.2d 290, 298 (Tenn. 1998) (“To hold otherwise would exalt form over substance.”); Henley v. Cobb, 916 S.W.2d 915, 916 (Tenn. 1996) (“it is well settled that Tennessee law strongly favors the resolution of all disputes on their merits”); Norton, 895 S.W.2d at 322 (Tenn. 1995) (emphasizing “the clear policy of this state favoring the adjudication of disputes on their merits”).

[5] King v. Pope, 91 S.W.3d 314, 325 (Tenn. 2002).