Strategic lawsuits against public participation—better known as “SLAPP-suits”—use the legal system to punish constitutionally protected speech.[1] The Tennessee Supreme Court has explained that “[t]he primary aim of a SLAPP is not to prevail on the merits, but rather to chill the speech of the defendant by subjecting him or her to costly and otherwise burdensome litigation.”[2] Using this definition, it is hard to argue that plaintiffs are engaged in anything other than quintessential SLAPP litigation when they: (1) sue someone for their speech; (2) run up a defendant’s litigation expenses for as long as possible before a hearing; and then (3) withdraw their claims just before a reviewing court can rule on them.

Fortunately, like many jurisdictions, Tennessee has enacted an anti-SLAPP statute called the Tennessee Public Participation Act, or the “TPPA.” As Tennessee’s Court of Appeals has explained, “the TPPA is largely intended to deter SLAPP lawsuits and prevent litigants from spending thousands of dollars defending themselves in frivolous litigation.”[3] “[T]housands of dollars,” it should be noted, is a dramatic undercount. Given Tennessee courts’ routine willingness to allow SLAPP-suit filers to delay proceedings through discovery, amendment, and other litigation tactics, the cost of defending a SLAPP-suit through a TPPA hearing routinely exceeds $25,000.00, and it often eclipses hundreds of thousands of dollars or, in some cases, millions.

In theory, the expenses imposed on SLAPP-suit victims do not matter at the end of the day. That is because the TPPA contains an expense-shifting provision—Tennessee Code Annotated section 20-17-107(a)—that requires trial courts to “award to the petitioning party: Court costs, reasonable attorney’s fees, discretionary costs, and other expenses incurred in filing and prevailing upon the petition[.]” Thus, no matter how long the litigation takes, the TPPA assures SLAPP-suit victims that they will recover their expenses at the end of it. As a result, assuming a plaintiff’s ability to pay the award, the TPPA promises SLAPP-suit victims that they will (mostly[4]) be made whole when litigation ends.

Unsurprisingly, those who are engaged in abusive litigation that is intended to burden speakers with uncompensated expenses are uninterested in paying their victims. And to achieve their nefarious goals, they have employed a simple tactic: file SLAPP-suits; run up a defendant’s litigation expenses for as long as possible; and then voluntarily dismiss their claims on the eve of hearing before a court can rule on them. Lawyers who make SLAPP-suits their business also have employed this tactic over, and over, and over again, often nonsuiting literally minutes before hearing, the night before hearing, or even during a hearing on a TPPA petition. After doing so, they have insisted that SLAPP-suit victims are not entitled to recover a penny of their legal expenses, because the voluntary dismissal precludes all further litigation, and a court has never granted a petitioner’s TPPA petition.

If blessing such a tactic seems antithetical to what the TPPA was designed to accomplish, that is because it is. Filing a bogus speech-based lawsuit, imposing substantial litigation expenses, and—recognizing that one’s claims have no chance of prevailing—dismissing the case right before a court can rule is definitionally the behavior that the TPPA was designed to deter. Even so, dozens if not hundreds of plaintiffs have done exactly that in the short time since the TPPA was enacted in 2019.

The certainty of fee-shifting also is what permits lawyers to defend SLAPP-suit victims on a contingent basis. Without contingency representations, SLAPP-suit victims would be forced to expend—upfront—tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of dollars to defend their speech against bogus lawsuits: an amount of money that few speakers have to spend even if they wanted to. Further, when faced with the choice of taking down a negative Yelp! review or having to liquidate one’s life-savings to defend it, self-censoring to avoid (or end) litigation becomes an easy choice.

Sadly, in a unanimous October 9, 2024 opinion authored by Justice Jeffrey S. Bivins, the Tennessee Supreme Court has now blessed the tactic of filing SLAPP-suits, running up litigation expenses, and then parachuting out of the litigation without consequence by nonsuiting on the eve of hearing. The opinion arose out of the most sympathetic facts possible: a misbehaving landlord filing facially meritless litigation against speakers who successfully advocated for tenants that the landlord had tried to evict illegally—outside the legal process and in contravention of a federal eviction moratorium—by cutting off their heat during the middle of winter. In response to TPPA petitions filed by those speakers, landlord Robert E. Lee Flade ran up the speakers’ litigation costs for roughly seven months; delayed a ruling following an initial TPPA hearing by convincing a trial court to allow him to take discovery first; and then voluntarily dismissed all of his claims just before a second TPPA hearing, leaving the sued speakers with tens of thousands of dollars in legal expenses that the Tennessee Supreme Court has now held they cannot recover due to Mr. Flade’s strategic dismissal.

The calamitous consequences of the Tennessee Supreme Court’s opinion in Flade—which strips the TPPA of its deterrent value—are assured. Simply put: No longer do calculated abusers of the legal system have to worry about being ordered to pay their victims’ legal fees. Instead, such abusers of the legal process are now empowered—as a matter of right—to file SLAPP-suits; wait and see if their victims are willing or able to hire an attorney to defend against them; run up their victims’ litigation expenses as long as possible before a TPPA hearing; and then voluntarily dismiss their claims before a court can rule. Because lawyers who defend SLAPP-litigation—even successfully—can no longer be assured that they will be paid for doing so, Flade also represents the end of SLAPP-suit contingency representations in Tennessee.

Confronted with the inevitable results of sanctioning this proven abuse, the Tennessee Supreme Court’s opinion explains that “[w]e do not intend to minimize [these] concerns. However, the[se] policy-based arguments are best addressed to the legislative branch.” Thus, according to the Tennessee Supreme Court, its hands were tied by the text of Tennessee Rule of Civil Procedure 41.01(1), which “permits liberal use of voluntary nonsuits at any time prior to ‘final submission’ to the trial court for decision in a bench trial or in a jury trial before the jury” absent certain specified exceptions.

Lest anyone be fooled, the Tennessee Supreme Court has never followed this approach to interpreting Rule 41.01(1) before now. For example, despite the Rule’s explicit prohibition against taking a voluntary dismissal “when a motion for summary judgment made by an adverse party is pending,” the Tennessee Supreme Court has held that “it is implicit in the Rule and inherent in the power of the Court that, under a proper set of circumstances, the Court has the authority to permit a voluntary dismissal, notwithstanding the pendency of a motion for summary judgment.”[5] The Tennessee Supreme Court has found other “implicit” exceptions to Rule 41.01(1)’s text, too, including inventing an entire category of exceptions for what it calls “The Vested Rights Implied Exception.”[6] Thus, far from interpreting Rule 41 in a way that ties the judiciary’s hands, the Tennessee Supreme Court has interpreted it atextually in a way that furthers judicial policy preferences throughout the Rule’s existence.

With these considerations in mind, no one should be misled by the Tennessee Supreme Court’s claim that this result was compelled by text. It was not—and the TPPA plausibly fell within three recognized exceptions to Rule 41.01(1) (two of them text-based) anyway. The Tennessee Supreme Court’s effort to distinguish as “inapposite” TPPA-based claims from several other claims that Tennessee law holds courts may adjudicate post-nonsuit—including claims “involving sanctions under Rule 11 of the Tennessee Rules of Civil Procedure,” “an award of damages for a frivolous appeal under Tennessee Code Annotated section 27-1-122,” and “legislation concerning ‘abusive civil actions’”—also demonstrates the malleability of the judiciary’s approach to the question presented by itself.

In summary, as it has before, the Tennessee Supreme Court made a policy choice; here, to defang the TPPA and reward those who file SLAPP-suits in Tennessee with the freedom to do so without fear of incurring consequences. The repercussions of that decision will be borne most heavily by the people who need the TPPA most—speakers of modest means who need lawyers to defend them on contingency—who will now be forced to incur significant debt to defend their speech; self-censor to avoid or end litigation; or defend themselves pro se. No one should celebrate this policy choice, and Tennessee’s free speech protection scorecard has now been downgraded as a result of it.

Read the Tennessee Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in Flade v. City of Shelbyville, No. M2022-00553-SC-R11-CV, 2024 WL 4448736 (Tenn. Oct. 9, 2024), authored by Justice Jeffrey Bivens, here: https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/OpinionsPDFVersion/Majority%20Opinion%20-%20M2022-00553-SC-R11-CV.pdf.

Questions about this article? Contact the author at daniel [at] horwitz.law.

Like ScotBlog? Join our email list or contact us here, or follow along on facebook at https://www.facebook.com/scotblog.org. You can also subscribe to the author’s aspirationally weekly newsletter on the Tennessee Court of Appeals—Intermediate Scrutiny—here: https://horwitz.law/intermediate-scrutiny-blog-signup-form/

[1] Daniel A. Horwitz, The Need for a Federal Anti-SLAPP Law, N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y Quorum (June 15, 2020), https://perma.cc/A8F4-FQ6G.

[2] Charles v. McQueen, 693 S.W.3d 262, 267 (Tenn. 2024).

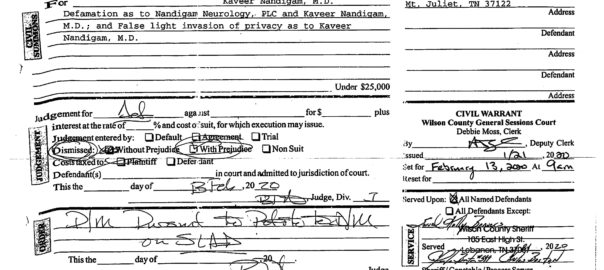

[3] Nandigam Neurology, PLC v. Beavers, 639 S.W.3d 651, 670 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2021)

[4] By statute, a defending litigant can only recover expenses “incurred in filing and prevailing upon the petition[.]” Tenn. Code Ann. § 20-17-107(a)(1). Thus, not all expenses are compensable, so the provision falls slightly short of this goal.

[5] See, e.g., Stewart v. Univ. of Tennessee, 519 S.W.2d 591, 593 (Tenn. 1974) (“it is implicit in the Rule and inherent in the power of the Court that, under a proper set of circumstances, the Court has the authority to permit a voluntary dismissal, notwithstanding the pendency of a motion for summary judgment.”); Anderson v. Smith, 521 S.W.2d 787, 790 (Tenn. 1975) (“where a summary judgment is pending, the right to a nonsuit rests in the sound discretion of the trial judge.”).

[6] Flade v. Shelbyville, No. M2022-00553-SC-R11-CV, 2024 WL 4448736, at *13 (Tenn. Oct. 9, 2024).